Disease Outbreak Investigation

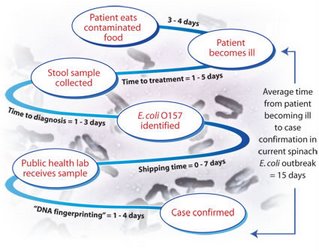

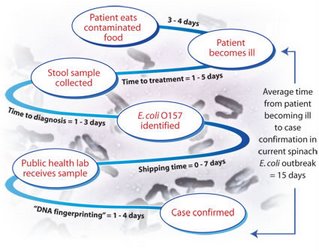

One of the questions that gets asked a lot is "why do we hear about outbreaks days to weeks after they start?" It's a valid question and is best explained by showing you a general timeline, borrowed from the CDC:

As you can see, there can be almost a two week delay from the time the patient consumed the infected food item to the time they are diagnosed. There is another factor that contributes to the apparent explosion in the number of cases once an outbreak is announced. Most cases of gastrointestinal upset are never seen by physicians. How many times have you had nausea, vomiting and diarrhea and never sought medical attention? Most of us decide to wait it out, sometimes with the assistance of over the counter medication (which can, in some instances actually make the situation worse). But once an outbreak is announced, people start considering that their recent GI upset might be related to the problem in the news and may seek medical attention. So more people get tested for the causative agent and the result is an increased number of cases appearing.

As you can see, there can be almost a two week delay from the time the patient consumed the infected food item to the time they are diagnosed. There is another factor that contributes to the apparent explosion in the number of cases once an outbreak is announced. Most cases of gastrointestinal upset are never seen by physicians. How many times have you had nausea, vomiting and diarrhea and never sought medical attention? Most of us decide to wait it out, sometimes with the assistance of over the counter medication (which can, in some instances actually make the situation worse). But once an outbreak is announced, people start considering that their recent GI upset might be related to the problem in the news and may seek medical attention. So more people get tested for the causative agent and the result is an increased number of cases appearing.

The vast majority of gastrointestinal upsets seen by a physician never have a stool sample collected. Interestingly, though most cases of diarrhea and vomiting are considered to be viral in origin, antibiotics are prescribed in a large number of cases. Antibiotics, of course, are useless in the treatment of viral diseases. Even more interesting, antibiotics can result in a more severe course of disease. Antibiotic use is associated with the development of hemolytic uremic syndrome in cases of enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) infection. Some individuals who acquire a Salmonella infection are able to shed the bacteria in their feces for an extended period of time, even after they recover completely from any symptoms of illness. Extended shedding of Salmonella is also associated with antibiotic use.

A brief bit of digression...

Why do I care about extended shedding of Salmonella if I'm no longer feeling sick? The answer is that you can be a source of infection for other people. If you fail to wash your hands thoroughly after using the bathroom or otherwise contaminate your environment (door handles, faucets, light switches) before washing your hands, you can transmit the bacteria to other people. Asymptomatic persons shedding Salmonella who work in food preparation, whether at home or at their jobs, can pass their infection on to many other people. This is similar to what happened with Typhoid Mary, though that particular case involved typhoid fever, which is caused by Salmonella typhi. In order to protect the public, most states now require food workers to have two or more negative stool cultures performed at a specified time interval before being allowed to return to work in food preparation.

Note: Typhoid fever in the US is relatively rare. Most Salmonella infections in the US are due to species other than Salmonella typhi. Common Salmonella involved in gastrointestinal disease belong to the serogroups Salmonella enteritidis and Salmonella typhimurium. (Yes, it's another of those complicated bacterial families. Perhaps in a few days I'll post "More than you ever wanted to know about Salmonella.")

Back to the Outbreak:

Outbreak investigations involve asking a lot of questions. If an outbreak is suspected of being related to food, the questionnaire will include questions about *everything* you ate during the potential exposure period. Not just what you ate that you think made you sick. That means remembering everything you ate for 2-4 days, sometimes as long as a week or two ago. This is harder to do than it seems at first glance. Try recalling everything you ate two days ago. Including snacks and incidental things, like the bite of your kid's snack or a piece of cake at work.

Other things that are asked about are the signs and symptoms of the illness: when did it start? what was the first symptom? how long did the symptoms last? when was the last episode of illness? did you see a physician for this disease episode? did you take any over-the-counter medication or herbal preparation for this illness? did you take any prescription medications for this illness? was a stool sample collected and cultured? do you know anybody else who has had these same symptoms in the past X days?

The questionnaire will also include some things which may or may not seem relevant to you: Have you visited a farm in the past X days? Have you had any contact with pets or farm animals in the past X days? If yes, what animals and when? Have you had any contact with reptiles (wild or pets) in the past X days? Have you had any contact with raw or undercooked meat or poultry in the past X days? Do you work in food service? Do you work in a day care center? Does any resident in your home attend or work at a day care center?

The next step is to compile all of the gathered data and try to find patterns and similarities in what was reported. We analyze what commonalities there are between the sick people. Did they eat at the same place? Did they eat the same food items? What common symptoms and test results were observed?

Usually a few things start to stick out as potential sources of infection. The next step is to find other persons who were potentially exposed at the same time and in the same way, but who did not get sick. It is very important to identify persons who are non-cases but had similar exposure history. We compare the proportion of people who ate a food and got sick to the proportion of people who did not eat a food but still got sick and also compare them to the people who ate the suspected food item and did not get sick. The items that stick out as possible sources of infection are the items which have a high proportion of people who ate them *and* got sick with a correspondingly low proportion of people who did not eat the item and did not get sick.

What complicates this process is that most people don't just eat a single item in a meal. Furthermore, some food items have multiple ingredients, any of which could be the source of infection. Add into the mix the fact that some foods share ingredients in common and the whole analysis becomes very complex and difficult to tease out the possible infection source.

All of these things contribute to the delay associated with not only identifying the presence of an outbreak, but also pointpointing its source. After all of that work is done, the work to investigate how the infection was introduced to that source and what can be done to prevent it in the future begins.

As you can see, there can be almost a two week delay from the time the patient consumed the infected food item to the time they are diagnosed. There is another factor that contributes to the apparent explosion in the number of cases once an outbreak is announced. Most cases of gastrointestinal upset are never seen by physicians. How many times have you had nausea, vomiting and diarrhea and never sought medical attention? Most of us decide to wait it out, sometimes with the assistance of over the counter medication (which can, in some instances actually make the situation worse). But once an outbreak is announced, people start considering that their recent GI upset might be related to the problem in the news and may seek medical attention. So more people get tested for the causative agent and the result is an increased number of cases appearing.

As you can see, there can be almost a two week delay from the time the patient consumed the infected food item to the time they are diagnosed. There is another factor that contributes to the apparent explosion in the number of cases once an outbreak is announced. Most cases of gastrointestinal upset are never seen by physicians. How many times have you had nausea, vomiting and diarrhea and never sought medical attention? Most of us decide to wait it out, sometimes with the assistance of over the counter medication (which can, in some instances actually make the situation worse). But once an outbreak is announced, people start considering that their recent GI upset might be related to the problem in the news and may seek medical attention. So more people get tested for the causative agent and the result is an increased number of cases appearing.The vast majority of gastrointestinal upsets seen by a physician never have a stool sample collected. Interestingly, though most cases of diarrhea and vomiting are considered to be viral in origin, antibiotics are prescribed in a large number of cases. Antibiotics, of course, are useless in the treatment of viral diseases. Even more interesting, antibiotics can result in a more severe course of disease. Antibiotic use is associated with the development of hemolytic uremic syndrome in cases of enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) infection. Some individuals who acquire a Salmonella infection are able to shed the bacteria in their feces for an extended period of time, even after they recover completely from any symptoms of illness. Extended shedding of Salmonella is also associated with antibiotic use.

A brief bit of digression...

Why do I care about extended shedding of Salmonella if I'm no longer feeling sick? The answer is that you can be a source of infection for other people. If you fail to wash your hands thoroughly after using the bathroom or otherwise contaminate your environment (door handles, faucets, light switches) before washing your hands, you can transmit the bacteria to other people. Asymptomatic persons shedding Salmonella who work in food preparation, whether at home or at their jobs, can pass their infection on to many other people. This is similar to what happened with Typhoid Mary, though that particular case involved typhoid fever, which is caused by Salmonella typhi. In order to protect the public, most states now require food workers to have two or more negative stool cultures performed at a specified time interval before being allowed to return to work in food preparation.

Note: Typhoid fever in the US is relatively rare. Most Salmonella infections in the US are due to species other than Salmonella typhi. Common Salmonella involved in gastrointestinal disease belong to the serogroups Salmonella enteritidis and Salmonella typhimurium. (Yes, it's another of those complicated bacterial families. Perhaps in a few days I'll post "More than you ever wanted to know about Salmonella.")

Back to the Outbreak:

Outbreak investigations involve asking a lot of questions. If an outbreak is suspected of being related to food, the questionnaire will include questions about *everything* you ate during the potential exposure period. Not just what you ate that you think made you sick. That means remembering everything you ate for 2-4 days, sometimes as long as a week or two ago. This is harder to do than it seems at first glance. Try recalling everything you ate two days ago. Including snacks and incidental things, like the bite of your kid's snack or a piece of cake at work.

Other things that are asked about are the signs and symptoms of the illness: when did it start? what was the first symptom? how long did the symptoms last? when was the last episode of illness? did you see a physician for this disease episode? did you take any over-the-counter medication or herbal preparation for this illness? did you take any prescription medications for this illness? was a stool sample collected and cultured? do you know anybody else who has had these same symptoms in the past X days?

The questionnaire will also include some things which may or may not seem relevant to you: Have you visited a farm in the past X days? Have you had any contact with pets or farm animals in the past X days? If yes, what animals and when? Have you had any contact with reptiles (wild or pets) in the past X days? Have you had any contact with raw or undercooked meat or poultry in the past X days? Do you work in food service? Do you work in a day care center? Does any resident in your home attend or work at a day care center?

The next step is to compile all of the gathered data and try to find patterns and similarities in what was reported. We analyze what commonalities there are between the sick people. Did they eat at the same place? Did they eat the same food items? What common symptoms and test results were observed?

Usually a few things start to stick out as potential sources of infection. The next step is to find other persons who were potentially exposed at the same time and in the same way, but who did not get sick. It is very important to identify persons who are non-cases but had similar exposure history. We compare the proportion of people who ate a food and got sick to the proportion of people who did not eat a food but still got sick and also compare them to the people who ate the suspected food item and did not get sick. The items that stick out as possible sources of infection are the items which have a high proportion of people who ate them *and* got sick with a correspondingly low proportion of people who did not eat the item and did not get sick.

What complicates this process is that most people don't just eat a single item in a meal. Furthermore, some food items have multiple ingredients, any of which could be the source of infection. Add into the mix the fact that some foods share ingredients in common and the whole analysis becomes very complex and difficult to tease out the possible infection source.

All of these things contribute to the delay associated with not only identifying the presence of an outbreak, but also pointpointing its source. After all of that work is done, the work to investigate how the infection was introduced to that source and what can be done to prevent it in the future begins.

Comments